|

Margate Crime and Margate Punishment

Anthony Lee

2. The Margate Constables.

The petty constables of Margate were responsible to the Deputy, who was also the High Constable. Although, in principal, the Deputy was chosen anew each year by the Mayor of Dover, from 1769 it was always a Cobb that was chosen; Francis Cobb the first (1727-1802), Francis Cobb the second (1759-1831) and Francis William Cobb (1781-1871) served as successive Deputies until the town became a corporate borough in 1857.1,2 It was Francis Cobb the first who established the family fortunes in Margate, the family becoming brewers, bankers, shipping agents, chandlers, coal merchants, insurance agents, ship owners, salvage experts, and owners of a considerable amount of property including many licensed premises, the outlets for the beer they brewed.

How well this early policing worked in Margate is unclear as few records have survived. The Margate Guide published in 1785 reported that Margate ‘is wholly destitute of any system of police’.22 In 1786 the Archbishop of Canterbury claimed, during a parliamentary debate on a bill for a theatre at Margate, that ‘Margate was not a chartered town, consequently it had not the benefit of a regular police’ and added that ‘there was no magistrate nearer than Dover, and it did not appear that they had given themselves the least trouble about the police of Margate for a very considerable period of time, if ever they did’.3 At about this time many towns had improved their policing by employing paid watchmen to patrol the streets, particularly at night. Such watchmen were often appointed under a private local Act and Margate obtained an act of this type in 1787.4 The Act established an Improvement Commission for Margate to oversee a range of improvements, including the appointment of a number of ‘able-bodied men, to patrol, watch, and guard the said streets, lanes, and passages.’ These watchmen were ‘authorized and directed to apprehend and secure, in the watch-house or some place of safety, all malefactors, disturbers of the King’s peace, and all suspected and other persons who shall be found wandering about or misbehaving themselves during the time of keeping watch, and to carry the person or persons so apprehended, as soon as conveniently may be, before some Justice of the Peace of the Town and Port of Dover, to be examined and dealt with according to Law.’ At the first meeting of the new Improvement Commissioners for Margate held on 6 June 1787 a Committee of fifteen commissioners was appointed, amongst other things, ‘to consider of the number of watchmen’.5 The earliest surviving letter of appointment for Francis Cobb as Deputy and High Constable, dated 1790, stressed that he was to ‘use [his] best endeavours that the King’s Majesty’s Peace may be kept within the said parish. And you are to arrest or cause to be arrested all such persons as you shall see or justly shall be complained of for making riots, assaults, or affrays in breach thereof, and also all Barrators [‘a malicious raiser of discord’] and Felons within the said Parish.The Deputy was also responsible for ‘apprehending, punishing, conveying and sending [away] all rogues and vagabonds and other wandering idle and disorderly persons’.6

Despite these expressions of good intent, not much seems to have been done. The first edition of Joseph Hall’s New Margate and Ramsgate Guide published in 1790 described how Margate ‘is subject to [Dover] in all matters of civil jurisdiction, a deputy from the Mayor of that town, resides in Margate, for the purpose of adjusting petty differences’.23 In the second edition published in 1792 this had been altered to ‘[Margate] is subject to [Dover] in all matters of civil or criminal jurisdiction; a deputy from the Mayor of that town residing at Margate for the purpose of regulating its internal police, and adjusting such disputes as may not be thought worthy the interference of the Bench at Dover.’8 However, in 1794 Hall wrote in a letter to Henry Dundas, the Secretary of State for the Home Department:7

as we have no Police here nor any Magistrate nearer than Dover, twenty three miles, all kinds of enormities are committed with impunity; the most daring outrages have lately been suffered by the inhabitants; on Friday evening the Treasurer’s office belonging to the Theatre Royal was broken open and all the cash and notes carried off. A pastry cook’s shop was forcibly entered and several articles of value taken away. I was myself most grossly insulted and abused ten days ago, without the least provocation, and tho’ I was at the expense of riding to Dover to make an affidavit of the transaction, the Mayor of Dover and his Deputy used every argument to deter me from prosecuting the offender, and after examination was allowed to return home; whether he gave creed or not I have not heard, but I should suppose not, as he is a fellow of a most infamous character…

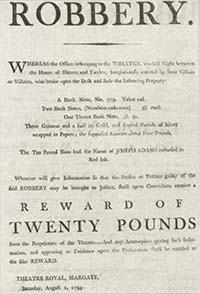

A poster was printed offering a reward of £20 to anyone providing information leading to an arrest for the robbery at the Theatre [Figure 1].

|

Figure 1. Poster asking for informational about the robbery at the Theatre Royal in 1794. [National Archives]. |

Perhaps Hall was being rather unfair in his letter to Dundas. The existence of at least some petty constables in Margate at this time is confirmed by reports in the local Press. One case was that of Vincent Andrews.9 Late one night in 1797 Andrews was set upon by ‘two ostlers and a gentleman’s servant,’ beaten and dragged into a ‘house of ill-fame’ where he was robbed of 30s. He was rescued by a member of the public, and then ‘the Constables assembled and took all three [men] into custody, and on being carried before the Mayor of Dover, he committed them to prison, for trial.’ Another case in November 1803, by which time Francis Cobb the second was Deputy, concerned Mr Lansell, a grocer and tallow-chandler in Margate who was briefly impressed by a Captain of the Royal Navy, leading a press gang in Margate. A correspondent to the Kentish Chronicle described the event as follows:10

The following are the particulars of this very extraordinary affair, as related to me by the parties who were the sufferers. About ten o'clock at night, Mr Lansell, who is a grocer and tallow-chandler, in an extensive line of business, was going round his premises with a lanthorn, as was his usual custom, to see every part safe from the danger of fire, he heard a voice exclaim, "Who is that fellow with the lanthorn?” Mr Lansell replied, "Who calls me that fellow?” The Captain instantly ordered his men to seize him, and take him to the boat. Mr Lansell informed him that he was a constable, and commanded the Captain in the King's name to keep the peace, and added that he was a tradesman, a housekeeper, and a volunteer, and in all those capacities exempted from the impress act. The only answer was, “D—n his eyes, take him on board." He was then dragged from his own door in the Market-place to the Pier, where he was overtaken by Mr Gore, the high constable [Thomas Gore was, in fact sub-Deputy, and presumably therefore sub-high constable], who is also a Captain of the Margate volunteers. Mr Gore interposed his authority, with his staff of office in his hand, upon which the Captain ordered his gang to seize Mr Gore, which was done accordingly, and he was dragged into the boat after Mr Lansell, where they were detained near two hours in the rain, under a guard of sailors, while the press-gang proceeded round the town, and pressed several other persons. Among the persons so impressed was Mr Brett, the farmer, of North Down, near Margate. The civil power was at an end; the officers of the law being impressed, Mr Brett had no one to apply to for protection, but was obliged to submit to the same violence that the other gentlemen had suffered. They were all taken on board the Texel, where Mr Gore happening to know the pilot, received from him some civilities. The Captain of the Texel was in bed, it being three o'clock in the morning when they reached the ship; but in justice to Captain Byng, who, upon this, as upon every other occasion, has conducted himself like an officer and a gentleman, it must be noticed, that he was no sooner informed of what had happened, than he invited Mr Gore and Mr Lansell to breakfast, and made them every apology, expressing the deepest concern for their sufferings, and informed them that his boat should take them on shore whenever they pleased to depart from the ship. — They were accordingly landed at Margate on the evening of the day after they had been impressed.

The number of constables in Margate at this time was probably small. It is known that in 1804 Francis Cobb the second asked for additional help in meeting the responsibilities of being High Constable and Dover agreed to his request to appoint John Curling Cobb, a distant relative living in Margate, to the position of assisting Constable. The Mayor of Dover wrote to John Curling Cobb on April 13 1804:6

Whereas on a representation made to us . . . by Francis Cobb Deputy and Constable of the Parish of St John the Baptist . . . that the said Francis Cobb not withstanding the aid and assistance of the Sub Deputy of the said parish is often under great difficulties in the discharge of his said office of Constable occasioned by an increase of disorderly people resorting to and residing within the said parish, wherefore he the said Francis Cobb hath prayed us to appoint you the said John Curling Cobb to act as an assisting Constable under the direction of him the said Francis Cobb and in his absence under the Sub Deputy of the said parish [and] . . . that you make diligent search in all suspected places within the said parish for all such rogues, vagabonds and sturdy beggars and other suspected and idle persons and in case you find any such that then you do apprehend and bring him her or them before the said Francis Cobb or in his absence before the sub-Deputy so as that such person or persons may be brought from thence by him or them to us or some other of his Majesty’s Justices of the peace for this town.

The Margate constables were sworn in each year at Dover, and the numbers of constables are included in a collection of payment books dating from 1807.11 In 1807, 11 constables travelled to Dover to be sworn in, at a cost of £13 13s to the parish of St John’s. The same number travelled in 1808, but by 1812 this had decreased to 6, increasing again to 8 in 1814, still being 8 in 1820; the numbers of constables did, however, increase later, to 18 in 1833 and to 20 in 1835.

The roles of the constables were made clear in two Parliamentary reports, into municipal corporations in 1833 and into municipal police forces in 1836. The Mayor and Town Clerk of Dover were asked by the Parliamentary Committee investigating the state of the Municipal Corporations in England and Wales in 1833 about policing in the limbs of Dover.12 Asked ‘Have the magistrates of Dover made any arrangements for the maintenance of the police within the liberties of Dover?’ they replied ‘Yes, within each limb there is a deputy appointed, which deputy exercises no magisterial authority; he is, in fact, the chief constable under the mayor and magistrates of Dover, or the Cinque Port magistrates residing in his neighbourhood; and besides the deputy in each limb there is a sub-deputy, and a certain number of persons called assisting constables, which number is indefinite; they generally depend on the recommendation of the parish officers as to the number required in each parish.’

The report of the Thanet Magistrates [see 6. Justices of the Peace at Margate] to the Royal Commission on Municipal Policing in 1836 gives a more detailed picture.13 Margate then contained about 2000 houses and had a population of about 11,600 with up to 8,000 more during the summer months. There were twenty one constables in Margate, nominated by the Margate Deputy but sworn in by the Mayor of Dover. The constables were paid no salaries but received payment from members of the public for serving warrants and summonses and for attending special sessions in Dover, but not for attending the weekly petty sessions then being held in Margate. Their main source of income was, however, payment for taking prisoners to Dover Gaol, paid for from the Dover Cinque Port Rate. Of these twenty one constables, ‘not much more than eight are much employed in the ordinary business’ and they received about £8 to £10 annually in fees. Some of the constables were also employed by the Pier Company carrying or protecting the luggage of the passengers using the steamboats. When asked ‘what class of persons is selected’ as a constable the magistrates replied that the constables ‘are usually from the lower order of tradesmen and labourers. They generally continue in office many years.’ Asked if there was a night patrol they replied: ‘In the town of Margate the Commissioners under a local act for managing the affairs of the Town have sometimes paid for a night patrol – they employed the constables and paid them out of the Town fund – at present there is not any such patrol.’

A paper in the Dover Assizes minutes for 1837 lists the constables in the Thanet division of Dover in July 1837, the parish of St. Johns having as well as the Deputy (Francis William Cobb), a Sub Deputy (John Jenkins) and 24 constables; the parish of St. Peters had 8 constables; Birchington had a Deputy, Sub Deputy and 2 constables; and Garlinge and Northdown had one constable each.14 The constables of St Johns were:

| John Knowler | Thomas Cleveland | Frederick Hare |

| Thomas Dunn | Henry Brown | John Weeks [or Wicks ?] |

| John Broome | Godfrey Faucit Westfield | Charles Mummery |

| Thomas G. Gore | George Gisby | James Ralph |

| James Pavey | John Boncy | James Fasham |

| John Paramor | Richard Crouch | Stephen Sackett Chancellor |

| Thomas Carter | James Mitchell | John Elgar Draper |

| William Knight | Thomas Dowson | Peter Major Jobson |

Seven of these names appear in Pigot’s Kent Directory for 1840 and include a builder, a stay maker, a fruiterer, a block maker, a restaurant owner, a shipping agent, and S. S. Chancellor, a collector of the Droits for the Pier and Harbour Company.15

The Thanet Magistrates reported that the constables were not proactive: ‘The constables do not generally apprehend offenders (except vagrants) but upon special application to them for that purpose’.13 The constables also made little attempt to capture any absconding offender: ‘there are not any means of promptly spreading information respecting any offence committed or of pursuing the offender’. Offenders trying to get away were likely to escape by sea to London or by road to Dover or Canterbury; the magistrates sometimes sent a Constable with a warrant to arrest one of these offenders but only if the offender was known to the constable. However, the magistrates reported that ‘stolen property is often found at the pawn brokers in a neighbouring town’, presumably a guarded reference to Ramsgate.

The Magistrates were uncertain about the strict honesty of the constables: ‘We are fearful that their connexions and interest may tempt them to connive at illegal practices in and respecting the beer houses and we have sometimes suspected that of the mendicants only the most miserable are brought before us whilst the hardy seasonal beggars find means of pacifying them, but we have no proofs — they seem always desirous to secure the committal of a prisoner — We are fearful they look to the allowance for taking them to gaol.’ The Magistrates also commented that ‘the constables seldom interfere with vagrants unless there is a probability of a committal — which is profitable to them’.

In reply to a question concerning the desirability of having paid constables, the magistrates suggested that about ten would be required and saw some advantages in having such a paid force: ‘a strong force is sometimes required to keep in control two or three violent persons in custody, particularly on the way from the Cage at Margate to the place of the Magistrates sittings — when the party is sometimes surrounded by a large concourse of riotous men and boys.’

In answer to a question about crime in Margate, the Magistrates reported that seventeen people had been committed for ‘felony or misdemeanour’ between November 1835 and November 1836. Most thefts in Margate were carried out by inhabitants ‘but some have been made by persons who do not generally reside in the district, but who are beggars usually visiting all the watering places in the proper season.’ There was a problem with crimes ‘common to unenclosed land, viz stealing of turnips and potatoes.’ In answer to the question ‘are there persons [in Margate] with no visible means of obtaining an honest livelihood?’ the Magistrates showed their frustration: ‘It is believed that there are many persons resident in Margate who have no visible means of subsisting but who live by habitual depredations or by illegal means (smuggling). We cannot state the number with any accuracy . . . Most of the depredations are of a petty nature, and committed by children with, as we are fearful, the knowledge and consent (perhaps the direction) of their parents – there may, we suppose, be five or six families of such description. As to the smuggling we believe that a great majority of the seafaring inhabitants never omit an opportunity of dealing in contraband goods, but the importation is very much checked by the Coast Guards.’ The Magistrates were also worried about the beer shops and public houses in Margate: ‘We have complaints that persons, and very young persons, are allowed to play at cards, as well in the houses having spirit licenses as in the beer shops, but it has not, in any instances, been proved before us that money has been staked on such play — We consider the practice as very dangerous to Society and we have repeatedly charged the constables to inquire and bring before us the offenders, and the owner of the House, and to watch that the beer shops are closed at the time directed by us — We do believe that if the constables had paid sufficient attention some of such offences would have been proved before us, but generally speaking the public houses are tolerably well conducted.’

The Royal Commission had a particular interest in how the magistrates dealt with any riots in the neighbourhood. The magistrates reported that in 1830 there had been many ‘tumults’ in the area, with threshing machines broken and ricks of hay and corn burnt. As well as the regular constables, the magistrates at time of need were able to swear in special constables although they ‘have not much reliance on their efficiency’; indeed, in 1829 and 1830 when the magistrates had to swear in some special constables, they ‘were obliged by reason of the pressure of the moment to swear all that offered and we found that several of the persons sworn had been in league with the rick burners.’ The magistrates relied more on their hope that ‘on representation to the Secretary of State or perhaps to the headquarters at Canterbury we may have military assistance.’

The Magistrates concluded their report with a complaint about the requirement to commit prisoners to the gaol in Dover, except for capital offences, where they had power to commit to the County Gaol in Maidstone. The cost of committal to Dover, including maintenance, was ‘40s for one prisoner and 20s every additional prisoner.’ This was paid for out of the Dover Cinque Port Rate, which, in turn, was taken from the poor rate collected in the Thanet Division of Dover. This, the magistrates estimated amounted to an average of £498 7s 6d per year and, they complained, ‘the inhabitants of the Liberty have no control over or even knowledge of the expenditure — except as to the allowance for taking persons to Dover Gaol, amounting to about £60 annually.’ The Cinque Port or Liberty Rate was set by the Borough Justices of Dover and the Thanet Justices had no power ‘of controlling or even being present at the making of the liberty rate’.16 In the years from 1836 to 1844 the contribution from Margate to this Liberty Rate varied between £464 and £619 per year.13,16

Although the Magistrates gave only faint praise to the constables, reports in the arraignment records of the Dover Quarter Sessions show that the job of a constable in Margate could be both hard and dangerous. One evening in March 1834, close to midnight, John Wicks, a Margate constable, was standing opposite the beer house kept by James Sands. Wicks reported that:17

Sands came out and as I passed we wished each other goodnight. Hogbin [another constable] was with me. We were on duty and Hogbin and I parted, he went one way and I the other. As I passed the Beerhouse I saw a light in the window, and whilst there Sands came out and asked me what business I had there. I said that was my business. He replied, “I’ll give you a bloody punch on the head", and I said, "Will you?" He then said again, "What business have you here?" I told him I was on my duty and not to interrupt. He immediately gave me a blow in the face with his fist. I then struck him with the staff I had in my hand. I then collared him and threw him down. We scuffled and I sprung my rattle for assistance. Hogbin came up and we took him to the Cage. As we were taking him down to the Cage he gave me two kicks on my leg so violently that the skin was broken. We were obliged to charge three or four persons for assistance in taking him down to the Cage.

John Wicks was attacked similarly in 1835. He reported:17

I am a Constable. Last night, about 12 o'clock, I was sent for by Mrs Harman and went. The two prisoners [Knocker and Warman] were trying to force their way into the house and wanting to fight with Mrs Warman. I persuaded them to go away. They told me I was one of the bullies, and I told them I was a Peace Officer. After repeatedly trying to persuade them to go away, Knocker struck me in the eye with his fist, then both set on me; they threw me down and both struck me. When I fell 15/6d dropt out of my pocket, and I have had 11/6d returned to me by persons who had picked it up. I saw the prisoner Warman pick up some. I followed them towards the Pier. They called five or six out of a fishing smack and persuaded them to throw me into the Harbour. They tried to drag me to the edge. I charged Mr Anderson for assistance, and he did assist me. And then Hogbin, another Constable, came up and we took the two prisoners to the cage. I am satisfied that they intended to throw me over the Pier.

John Anderson, a shoemaker living in Pump Lane, corroborated Wicks’ statement. 17 He explained that after Wicks had charged him for assistance, he persuaded Knocker and Warman to go away and they said they would not, ‘but would throw the B—r over the Pier.’ Anderson reported that they seemed ‘very resolute’ and he believed they intended to carry out their threat.

Both of these cases involved attacks at night, suggesting that John Wicks could have been one of the constables employed on the night patrols paid for by the Commissioners, as described above. In 1836 John Wicks was again attacked, this time in the afternoon:18

Yesterday… between 3 and 4 in the afternoon, the prisoner William Wilson was in my custody and by virtue of a warrant issued by Mr Nethersole [one of the Thanet magistrates] I took him to Mr Nethersole’s house, but he was not at home. The prisoner wished to stay there till Mr Nethersole came home, but I told him we must not wait there, but we must go away, until Mr Nethersole could see us. He stated he would remain there, or go where he pleased. I told him he must come with me. I proceeded to take him away and he resisted; he struck me several times with his fist on the side of my head and mouth, and the marks now there are the consequence of the blows which he gave me. I then told him he should go to the cage. I sent for John Boncy the constable to assist me. He did not appear to be at all in liquor.

Wilson was committed for trial at Dover by the Rev Francis Barrow, another of the magistrates.

On at least one occasion things get seriously out of control. 17 In March 1834, at a Petty Sessions in Margate held in the Public Office, two young men, John and George Beale, both Margate labourers, were being prosecuted by one of the Margate constables, Godfrey Faucit Westfield, for an assault on him in the execution of his duty. The magistrates, Mr Hannam and Mr Nethersole, found there was a case to be answered and ordered that the Beales be tried at the next Dover Sessions and that they be released on bail with personal sureties of £10 and two additional sureties of £5 each. This they refused to accept. The events that followed were described by John Boys, Clerk to the Magistrates, in a detailed minute:

It appeared to me as if one of them was going out of the office, upon which I said to the constables at the door “you must not let them go out” and immediately on my saying so, Mr Nethersole then gave some directions, which from the noise I could not hear distinctly; at this instant my attention was taken off by the Parish Officers who had other business and whilst so engaged I heard George Beale say to Mr Hannam (who was Chairman for the day) that he “could not see straight” and a deal of other insolence followed, with repeated refusals to find bail, and accompanied by oaths — one expression was, that Mr Hannam’s name “stunk in the Isle of Thanet.” There was then a general noise and confusion from the many persons talking together and when this subsided a little I once more asked the prisoners if they “meant to find bail or not”. One of them said “no I’ll be dd if I do.” I then told the constables they must be removed to make room for other business, upon which Boncey (a constable) with his left hand took hold of John Beale’s coat, to pull him forward — and immediately John Beale struck Boncey’s hand away and said “none of that or I’ll give it you” clenching his fist at him. Boncey then tried to lay hold of John Beale again, when John Beale violently thrust his hands at Boncey to force him away; on seeing this Brown (another constable who was close behind Boncey) drew his staff out, which John Beale seeing called out with great vehemence “down with that thing, or I’ll d—d soon have it away from you” and advanced towards Brown as if to perform this threat, and at the same moment a burst of noises came from the spectators behind — Boncey than again seized John Beale and there was immediately a cry just without the Office door of “Rescue, Rescue” and within the office “go it, go it” and various other noises. Upon which Edward Knott [a cordwainer19] made a dash forward and tried to throw himself between Boncey and John Beale and a struggle ensued between John Brown and Knott on the one side with Boncey and Brown on the other; this induced Evestfield (another constable) to rush forward from my side of the office and he pulled John Beale backwards and threw him down on the floor.

At this instance my desk was nearly overset by George Beale and Wicks, the constable, who were in conflict under it; and I got up on my seat to command a view of every person in the office most of whom were well known to me (for I was not alarmed) — the whole office was then in commotion, and my attention was turned to Brown the constable and Knott who were both down on the steps which lead from the public office to the private room; Knott appeared to have got Brown completely under him — I think the Magistrates at this moment had all retreated into the inner Room — It was several minutes before the prisoners were sufficiently exhausted by their violence to be mastered by the constables, and which they (the constables) could not have done if they had not got them (the prisoners) into handcuffs. At this time Beale’s wife was in fits in the Inner Office — in about ½ an hour (I think) a fish cart and four constables got the prisoners away for Dover Gaol. There was great shouting and yelling in the streets at their departure, but the Office Doors were barricaded and the mob kept out; there was much blood spattered all over the office which took about an hour to wash and clean the following morning, and the inner door latch was broken off. The rest of the business of the day was unavoidably postponed.

The constable Henry Brown described his struggle with Edward Knott:

Edward Knott was urging them on to resistance and he was approaching towards the prisoners when I lifted up my staff in my hand to keep him back, and he snatched my staff out of my hand. I then collared him and Dunn, another constable, came up to my assistance. We then tried to get Knott into the Magistrates private room and as soon as we got him in he pushed us down on the floor and put my staff across my throat and pressed it hard. I got hold of the staff and with Dunn’s assistance I released myself from the pressure of the staff. This happened whilst the magistrates were in attendance at the office and it retarded the business of the day; I was not hurt excepting by the face.

The Kent Herald reported that rioting continued outside as the Beales were being put into the fish cart:20

Upon being placed in [the cart] and a constable named Brown attempting to get into it, they attacked him in the most wanton manner, and finally succeeded in ejecting him from the vehicle into the road; upon this the mob, amounting to upwards of 300 persons, began to assail him with stones and other missiles, until he took shelter in the house of another constable, when they quietly dispersed.

Finally, at the Dover General Sessions in April George and John Beale were found guilty of committing a violent assault on Westfield and Edward Knott was found guilty of attempting to rescue the Beales and of assaulting Henry Brown.21 Although the prisoners regretted ‘their violence in the magistrates office . . . and [expressed] their sorrow for the offensive language used at the time’, all three were sentenced to six months with hard labour

References

1. W. F. Cobb, Memoir of the late Francis Cobb of Margate, Maidstone, 1835.

2. Kent Archives, U1453/Z148, Cobb family tree.

3. Parliamentary Register 1780-1796. Sixteenth Parliament of Great Britain: third session (24 January 1786 - 11 July 1786), May 3 1786.

4. An Act for rebuilding the Pier of Margate in the Isle of Thanet . . . for widening, paving, repairing, cleaning, lighting, and watching the streets, lanes, highways, and public passages in the town of Margate, 2 Geo III, cap 45, 1787.

5. Edward White, Extracts from the minutes of the Margate Commissioners, Book 1, 6 June 1787 to 12 November 1788, Manuscript in Margate Library.

6. Kent Archives U1453/O35/9, Appointment by Francis Cobb of John Curling Cobb 1804.

7. National Archives, HO 44/33/8 fo 22, Letter from Hall to the Right Hon Henry Dundas, August 3 1794.

8. J. Hall, Hall’s New Margate and Ramsgate Guide, Margate, 2nd edition, 1792.

9. Kentish Gazette, October 6 1797.

10. Kentish Chronicle, November 18 1803.

11. Kent Archives, U1453/O45, Deputies Accounts.

12. Parliamentary Papers. Report from the Select Committee on Municipal Corporations; with the minutes of evidence taken before them, 1833.

13. National Archives, HO73/5 Box 2, Return of Justices of the Isle of Thanet to the Constabulary Force Commission, Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire as to the Best Means of Establishing an Efficient Constabulary Force PP 1839 XIX [169], p 1 Returns from local guardians. Cinque Ports – Thanet Division of Dover.

14. Kent Archives, Do/JQ/n2, Dover Assizes Rough session minutes 1837-1838.

16. National Archives, TS25/192, Lock-up House, Margate.

17. Kent Archives, Do/JS/d11, Informations etc before the Cinque Port Justices 1828-1836.

18. Kent Archives, Do/JQ/d1, Dover Assizes, Original depositions 1836.

19. Kent Archives, Do/JS/n5, Dover Assizes, 1834 draft general sessions minutes.

20. Kent Herald, March 20 1834.

21. Dover Telegraph, April 5 1834.

22. The Margate Guide containing a particular account of Margate . . . , Thomas Carnan, London, 1785.

23. J. Hall, Hall’s New Margate and Ramsgate Guide, Margate, 1st edition, 1790.